Philosophy Toolkit

Welcome to the Philosophy Toolkit

A searchable index of philosophical lesson plans

The Philosophy Toolkit contains over 250 lesson plans to inspire philosophical discussions with students of all ages. Please explore this free searchable resource, starting with our Getting Started pages below. Contact us with any suggestions or reactions.

The Philosophy Toolkit contains over 250 lesson plans to inspire philosophical discussions with students of all ages. Please explore this free searchable resource, starting with our Getting Started pages below. Contact us with any suggestions or reactions.

Our Links page also offers links to other sites with high quality lesson plans and other resources for philosophy with young people.

We welcome lesson plan submissions for the PLATO Philosophy Toolkit. Submissions should include: grade level, time necessary for the lesson, area, and topics (see other Toolkit lesson plans). Submissions are accepted for review year round. Please submit lesson plans to Education Director Karen Emmerman at karen@philosophy-plato.org.

Looking for resources on philosophy and children’s literature?

The Philosophy Toolkit includes over 100 lesson plans for children’s books!

Click here to browse Philosophy and Children’s Literature →

We have also developed prompts for reflecting about difficult issues, such as anxiety, death, loneliness and boredom. Click here to browse those.

- Art

- Film

- History and Social Studies

- Language Arts and Literature

- Math and Logic

- Music

- Science

- Other Areas Clear Area Filter

- Preschool

- Primary & Elementary School

- Middle School

- High School & Beyond Clear Area Filter

- ethics (48)

- Epistemology (24)

- metaphysics (18)

- Fairness (15)

- reasoning (14)

- morality (11)

- Beauty (10)

- Identity (10)

- art (9)

- Friendship (9)

Recently Added:

Getting Started:

Getting Started

The Philosophy Toolkit contains a variety of different lesson plans for leading philosophical discussions with young people. Each lesson plan indicates the grade level for which it is appropriate as well as an estimate of the time necessary to complete the lesson. Please explore the Toolkit and contact us with any suggestions, questions, or feedback.

Search by Areas and Grade Levels:

The Toolkit is organized by Area and Grade Levels. In the navigation on the left, you can click “Areas” to get a drop-down menu of academic topics (e.g., History and Social Studies, Science, and Music).

If you would like to search by the age range of the students you work with, click on “Grade Levels” to open a menu listing grades from preschool through high school and beyond.

Search by Philosophical and Other Topics:

If you are looking for lesson plans focused on a particular philosophical area (e.g., ethics, metaphysics, epistemology, and aesthetics), simply enter that term into the search bar to receive a list of lesson plans with that philosophical focus.

If you prefer to search for a more general topic (e.g., friendship), enter any search term you like and receive a list of lesson plans related to that topic.

Popular Topics

Looking for inspiration? Take a look at some popular lesson plans from recent user searches by clicking the “Popular Topics” tab in the navigation bar on the left.

It’s important that the teacher/facilitator always keeps in mind that the whole point of doing philosophy with young people is to help the students develop their own thinking! The role of the teacher/facilitator is guide the discussion without attempting to control its content. In other words, do not plan to dictate the substance of the discussion, but rather provide the tools and structure for the discussion to take place among the participants/students.

Remember it’s a balancing act between helping students achieve philosophical clarity and depth and refraining from imposing on the conversation your own preferences for subject matter. This requires sensitivity, skill and practice; push too hard and you’ll monopolize the conversation, but if you do not provide enough structure the students can end up following tangents at length or simply engaging in an opinion-sharing exercise, and making no progress!

To assist you in getting started, we have compiled a list of things to do and not to do that we have found helpful for new and experienced philosophy educators alike.

Things To Do

Hint: Let the discussion flow from the students’ questions and ideas. After reading a story or doing an activity, ask, “What questions did this make you think of?”

- Encourage the students to build on each other’s ideas.

- Show the students that what they say makes you think.

- Encourage the students to speak to one another.

Things Not To Do

- Tell the students their answers are right or wrong.

- Plan to teach the students some philosophical argument or point.

- Insist on your own views.

- Be uncomfortable with or try to fill-in intervals of silence.

- Give a definitive answer to a philosophical question.

- Permit lengthy discussions of relatively unimportant issues.

- Monopolize the discussion.

- Resolve issues for them.

- Try to show the students how philosophically sophisticated you are.

The Difference between Philosophical & Non-Philosophical Questions:

Ten Examples of Philosophical Questions

- Are numbers real?

- Do animals think?

- What is a thought?

- Why I am alive?

- What makes someone a good friend?

- How do we know anything?

- What makes a life a good life?

- How should human beings treat the environment?

- What does it mean to be brave?

- What is time?

Ten Examples of Non-Philosophical Questions

- What is 10 x 10?

- How many bats are there in the state of Pennsylvania?

- How do computers work?

- How does the brain work?

- Do sea cucumbers have brains?

- What is the capital of Bulgaria?

- How much pollution do humans contribute to the Earth?

- Is the death penalty legal in Sweden?

- How many people live in Nigeria?

- When was the Declaration of Independence signed?

Good Leading Questions to Ask in a Philosophy Session:

- “What did you mean when you said . . .?”

- “That’s an interesting idea. Can you explain what you were thinking when you said that?”

- “When you said . . . , did you mean . . . ?”

- “How does what you just said relate to what ____ said a moment ago?”

- “So if what you just said is true, is ____ also true?”

- “When you said ____, were you assuming ____?”

For more thoughts on how to facilitate philosophy sessions with young people, read this article on “The Cultivation of Philosophical Sensitivity”

Most classroom philosophy sessions are arenas for discussions about the ideas and questions of philosophy, as opposed to being primarily focused on what historical and contemporary philosophers have to say about these ideas and questions. That is, we engage young people in the practice of philosophy. A powerful model for this educational approach is the community of philosophical inquiry.

Lipman and the Community of Inquiry

Matthew Lipman’s detailed conception of the community of inquiry—in which students and teacher(s) learn from one another— was among his most significant contributions to the field.

The community of inquiry, as Lipman conceived it, includes the following characteristics:

- The enterprise is based on mutual respect;

- The students build on one another’s ideas and follow the argument where it leads;

- Students challenge each other to supply reasons for their opinions;

- Students assist one another in drawing out inferences from what has been said; and

- Students endeavor to identify one another’s assumptions.

The members of the community of inquiry come together in a spirit of intellectual freedom to explore the more problematic and puzzling aspects of situations and curriculum concepts, rather than emphasizing the “facts.”

The Community of Philosophical Inquiry

The community of inquiry model can be used to explore any subject matter in the classroom. The special features of a community of philosophical inquiry (CPI) involve the content (i.e., philosophical topics). Philosophical topics examine meanings, attempt to clarify concepts, and generally engage abstract questions whose answers are contestable, rather than final or settled.

In a CPI, the students’ philosophical questions shape the scope of the inquiry. Teachers guide the students in inquiry, but do not control the content of the discussion and often don’t know ahead of time what the topic or topics under consideration will be.

The teacher’s role here is robust, but subtle. Teachers pay close attention to the initiation and progress of the dialogue, look for connections among what students say, ask for clarification and reasons, and are attuned to the philosophical content of questions and ideas that might otherwise be lost. This entails a delicate balance between supporting students’ attainment of philosophical clarity and depth and refraining from imposing the teacher’s own preferences for subject matter and the direction of the discussion.

Central features of a Community of Philosophical Inquiry (CPI)

- The content is philosophical: Members of a CPI are engaged in a structured, collaborative inquiry aimed at building meaning and acquiring understanding through the examination of philosophical questions or concepts of interest to the participants.

- Epistemic Modesty: A CPI entails a consensus of ‘epistemological modesty’—an acknowledgement that all members of the group, including the facilitator, are fallible, and therefore hold views that could end up being mistaken. Teachers in a CPI facilitate students’ ability to think for themselves about the fundamental aspects of human existence. We demonstrate a reticence about advocating for our own philosophical views and model a comfort with uncertainty and with the fact that we don’t have final settled answers philosophical questions.

- Avoiding the use of jargon: Participants in a CPI generally refrain from using much technical philosophical language or referring often to the work of professional philosophers. This helps to ensure that the group focuses on exploring the questions themselves and not the past or current history of the subject among professional philosophers.

- Intellectual Safety: The CPI is an environment of intellectual safety, one in which any question or comment is acceptable, so long as it does not belittle or devalue others in the group, and which allows trust and a corresponding willingness to present one’s thoughts to participants. The teacher models openness and respect for others’ ideas and constructs a structured space that invites the students to engage thoughtfully and with an appreciation for multiple perspectives

While an intellectually safe learning community involves trust, respect, and an atmosphere conducive to taking intellectual risks, it does not promise comfort. Communities of inquiry are dedicated to the open and rigorous exploration of difficult and contestable issues and the intellectual growth that results, the process of which can often provoke feelings of perplexity and uncertainty. This can be an uncomfortable experience. Feeling intellectually safe, therefore, is not to feel complacent or unchallenged—it is to feel supported in one’s struggles to make sense of the world for ourselves.

One practical tool to begin to fashion an intellectually safe atmosphere is to help the students set the rules for the community of inquiry at the beginning of the year. The rules can be posted so that they are always visible during philosophy sessions, and you can remind the students of them from time to time.

Ethics

Warm-up #1:

Think of someone you know who you think is a really good person. What makes that person a good person?

Warm-up #2:

• Think of something that’s pretty good.

• Now think of something that’s better than pretty good, that’s good.

• Now think of something that’s better than that, that’s really good.

• Think of something that’s pretty bad.

• Now think of something that’s worse than pretty bad, that’s bad.

• Now think of something that’s worse than that, that’s really bad.

• Now think of something that’s both good and bad.

• Now think of something that’s neither good nor bad.

Warm-up #3:

• Do you have memories that make you feel a certain way?

• Can you have a memory that makes you happy?

• What is happiness?

• Can you be happy but feel sad?

• Can you feel sad but be happy?

• Can you be happy and sad at the same time?

• What makes you happy?

Warm-up #4:

Think of something:

• You’re glad has happened

• You wish had happened

• You wish hadn’t happened

• You’re glad didn’t happen

Epistemology

Warm-up #1:

• Think a big thought (about something small)

• Think a small thought (about something big)

• Think a really hard thought (about something soft)

• Think softly. Can you?

• Think a funny thought

• Think a serious thought

• Think of a part of your body: think of your foot

• Think of your hand

• Think of your head

• Think of your mind: What is your mind?

• Think of something that’s true: What is true?

• Think of something that’s false: what is false?

• How do you know the difference between true and false?

Warm-up #2

• Think the biggest thought you can.

• Think the tiniest thought you can.

• Think the oldest thought you can.

• Think the newest thought you can. Can you think of an even newer one?

• Think of something really good.

• Think of something really bad.

• What makes something good or bad?

Warm-up #3:

Let’s start by all thinking together.

What’s a thought we can share?

• Can we all think about the same thing?

• Let’s all think about the sky. Are we all thinking the same thing?

• Let’s all think about a dog. Are we all thinking the same thing?

• Can we all have different thoughts? Is it possible that every one could think of something different?

• What are you thinking about right now? What about now?

• How long is now?

Warm-up #4:

• Let’s all think really really hard…about something really soft.

• Let’s all have really big thoughts…about something small.

• Let’s all think of the same thing

• Let’s all think of something different

• What’s your favorite thought?

• What’s your least favorite thought?

• Let’s all think about something we know.

• What is something we wonder about?

• Do you ever wonder what it means to be a friend?

• What can you be friends with?

Warm-up #5:

• Think of something in the past

• Think of something in the future

• Think to yourself

• Think to someone else

• Think something you know

• Think something you don’t know

• What makes something what it is?

• What makes a duck a duck?

• What makes a chair a chair?

• What makes your teacher your teacher?

Warm-up #6:

• Think the biggest thought you can.

• Think the tiniest thought you can.

• Think the oldest thought you can.

• Think the newest thought you can. Can you think of an even newer one?

• Think of something about yourself.

• Think of something about someone else.

• What’s the difference between you and someone else?

• What makes you you?

Warm-up #7:

Let’s start by wondering. What are you wondering about?

• Can you wonder about what you’re wondering about?

• What are you thinking about? Can you think about what you’re thinking about?

• How many of you are thinking about tomorrow? What’s it like to think a thought about the future?

• Can you think a thought about the past?

• What are thoughts like? What are they made of? Can you build thoughts?

• Think of an elephant. Now put a hat on it. Now, on top of the hat, put a bird. Now change the color of it.

• What color are thoughts? Can you think a green thought? A red thought? What about a super-bright thought?

• Can thoughts make you feel things? Can a thought make you happy? Can it make you laugh? What about scared? Can a thought make you scared?

• Here’s a story…

• When it’s dark out, I….

Warm-up #8:

• Let’s all think. What are you thinking about?

• Can you think about what you’re thinking about?

• Let’s try wondering. What are you wondering about?

• Can you wonder about what you’re wondering about?

• Do you ever wonder about what is real?

• What’s something that’s real?

• What’s something that isn’t real?

• Can you think of something that isn’t real, but seems real?

• Can you think of something that is real but doesn’t seem real?

• How can you tell if something is real?

• Are dreams real?

• Are thoughts real?

• Are you real?

• Something I wish that was real is…

Warm-up #9:

• Is anyone NOT thinking?

• What are you NOT thinking about?

• Do you ever think about yourself?

• When you think about yourself, what do you think about?

• Can you think about your foot? Your hand? Your head?

• Can you think about your mind?

• When you think about your mind, what is doing the thinking?

• Can you imagine you were something else? What?

• Can you imagine your were nothing? If you were nothing, what would you be?

• Do you ever wonder who you are?

• How do you know who you are?

• Could someone convince you that you weren’t you? How?

• When I think of myself, I know…

Warm-up #10:

Write down something you believe and something you know.

How do you know the difference?

Warm-up #11:

• Write down something you know about yourself.

• Write down something you don’t know about yourself.

• Write down something pretty much everyone who knows you knows about you.

• Write down something hardly anyone who knows you knows about you.

Warm-up #12:

Think of someone you think of as a really good friend. What makes this person a good friend?

Aesthetics

Warm-up #1:

Write down something that you think is beautiful and two reasons why you think it’s beautiful, and write down something that you think is ugly and two reasons why you think it’s ugly.

Warm-up #2:

What is your favorite art form (music, literature, visual arts, dance, poetry, film, theater, etc.)? What about it do you like most?

Warm-up #3:

Think of something (and write down if appropriate):

• Visually beautiful

• Visually ugly

• Tastes delicious

• Tastes disgusting

• Smells fragrant

• Smells stinky

• Feels really good

• Feels really awful

• Sounds great

• Sounds terrible

Warm-up #4:

• Think a red thought

• Think a blue thought

• Think a green thought

• Think a yellow thought

• Think a purple thought

• Think an orange thought

• Think a clear transparent thought

Metaphysics

Warm-up #1:

If you had to describe yourself using only 5 words, what would they be? Write them down.

Warm-up #2:

• Think of something that’s real.

• Is there a way it might not be real?

• Think of something that’s not real.

• Is there a way it could be real?

Warm-up #3:

Think of (and write down) something that happened (or is happening)

• In the present

• 1 minute ago

• 1 hour ago

• 1 day ago

• 1 year ago

• 5 years ago

• 10 years ago

• Your earliest memory

• Now, return to the present and think of something:

• 1 minute from now

• 1 hour from now

• 1 day from now

• 1 year from now

• 5 years from now

• 10 years from now

• As far in the future as you can imagine

Warm-up #4:

Think of:

• Something that is

• Something that was

• Something that will be

• Something that won’t be

• Something that could be

• Something that can’t be

• Something that should be

• Something that shouldn’t be

• Something you wish was

Warm-up #5:

Think of:

• Something that exists

• Something that doesn’t exist

• Something that might exist

• Something that might not exist

• Something that could exist be doesn’t

• Something that doesn’t exist but could

• Something that used to exist

• Something the will exist

• Something you wish existed

Social and Political Philosophy

Warm-up #1:

• Think of something that’s fair.

• Think of something that’s unfair.

• Think of something that’s both fair and unfair.

• Think of something that’s neither fair nor unfair.

Warm-up #2:

If you had the power to decide on one rule that should govern society, what would it be?

Critical Thinking

Warm-up #1:

• Think about something

• Remember something

• Wonder about something

• Think about thinking

• Remember about remembering

• Wonder about wondering

• Think about remembering

• Remember about wondering

• Wonder about thinking

• Think about remembering about wondering

• Remember about wondering about thinking

• Wonder about thinking about remembering

Warm-up #2:

• Wonder why

• Wonder how

• Wonder what

• Wonder when

• Wonder who

• Wonder if

Philosophy can be a powerful way for groups to think about issues related to historical and contemporary injustice, exclusion, oppression, and domination. The community of philosophical inquiry can be a helpful format for considering these kinds of complex issues, particularly in the wake of local and national events that warrant reflection and discussion. There are numerous materials practitioners can use to prompt conversations about social justice topics. Before doing so, it is important for facilitators to ask themselves several questions.

Who decides to have this conversation?

The direction of the discussion is determined by the students and not the facilitator. Facilitators can choose a prompt that might stimulate discussion of social justice topics but should not impose their desire to address those topics or their own views of the topics. Students may raise questions unrelated to questions of social justice and wish to discuss those. They have authority over what conversation to have.

Who needs to have this conversation?

We often think about philosophical discussions about social justice issues as “important,” but we must ask ourselves: important for whom? Think carefully about who actually needs to have the conversation you are planning to facilitate. Is it the students from marginalized groups in the room? The students from privileged groups? For example, facilitators often think it is important to discuss race. That is correct as far as it goes, but it is critical to ask oneself who needs to talk and think about race, and with whom. This relates to the third question facilitators should ask themselves.

Who is in the room?

Rather than thinking “this is an important topic to think about with students!” ask yourself “is this an important/valuable/appropriate topic to discuss with these students?”. For example, leading a discussion about race in the United States in a classroom where most students are white and only a few are Black or Brown can be problematic for several reasons. First, students of color already must think about race as they navigate the world day to day. Thinking about race is not novel for them and they may in fact prefer philosophy to be an escape from those burdens. Second, in a classroom that is majority white, Black and Brown students can often be problematically tasked with speaking for the perspectives of marginalized groups. It is not their job to do so, nor should philosophical discussions put them in that position. Finally, it is problematic to subject students from marginalized communities to privileged students’ learning process regarding the injustice in question. For students living with a disability, for example, it is not a learning or growth opportunity to hear other students work through the realization that people with disabilities live rich and varied lives. Facilitators should think about who needs to have the conversation they propose having and how those in the room who may be impacted negatively by such conversations.

How are you, the facilitator, situated relative to the students in the room?

It is critical that facilitators consider their own positionality when planning to discuss topics about social justice issues. Are you a member of the community most impacted by the injustice to be discussed? If not, are you a member of a community that has some responsibility (past or present) for the injustice you would like to discuss? What are the social, racial, religious, and cultural ways in which you are different from your students that are relevant to how they will experience the discussion? For example, for a non-Jewish person, discussing a recent synagogue shooting is very different than it is for Jewish students who may feel fearful for their and their loved ones’ safety when they go to synagogue.

You may need to think about whether you are the best or even an appropriate person to facilitate the discussion. If you are not the classroom teacher, it can be helpful to check in with them to find out if the topic is already under discussion, how it is going, and how the students are doing. It can help to overtly raise the issue of your own positionality and express your understanding that you do not experience the topic to be discussed in the same way as your students. Always be ready to pivot to a different stimulus or topic if students are showing signs of problematic discomfort (some discomfort is normal for philosophy). Commit to listening, taking ownership and apologizing when you are wrong, and saying that you are willing to learn. Finally, engaging in pedagogy research that discusses teacher positionality and how that can impact students’ experiences is a helpful way to gain information and insight into how best to handle these discussions.

What is the power dynamic between you and your students?

By virtue of being adults and being in a facilitation role, P4C facilitators are already in a position of power relative to the students. This is true even when we work assiduously to decentralize the classroom. There may also be other relationships of power in the room, depending on what privileges the facilitator has that the students do not (e.g., race, class, gender, etc.). Differences in power can influence whether and how students share their thinking. Responding to age/power differences is often also mediated by culture. This is all important to consider before embarking on a discussion related to social justice.

How can you help the students end the session feeling healthy and safe?

Should you decide to proceed with the discussion, it is important to make a plan that leaves time for self-care practices at the end. Pick an activity that encourages movement, mindfulness, journaling, energy building, or connection to help students close out the session in a healthy way.

Developing an awareness of the philosophical dimensions of our lives – sometimes characterized by philosopher Jana Mohr Lone as developing “philosophical sensitivity” – is a key outcome of engaging in philosophy at an early age. For example, as children learn to recognize when situations have an ethical dimension, they begin to appreciate that how they respond in such situations will help determine both whether those situations become more or less good, right or just, and the kind of persons they are becoming.

![]() The central method of philosophical inquiry is careful, logical, and rational thinking.

The central method of philosophical inquiry is careful, logical, and rational thinking.

Philosophy has always been preoccupied with good thinking, with logic being one of its oldest branches. While formal logic is beyond the skill of most young children, they are very capable of the informal logical operations that constitute basic reasoning, including:

- Giving reasons

- Considering evidence

- Agreeing and disagreeing

- Giving examples and counter-examples

- Making comparisons and distinctions

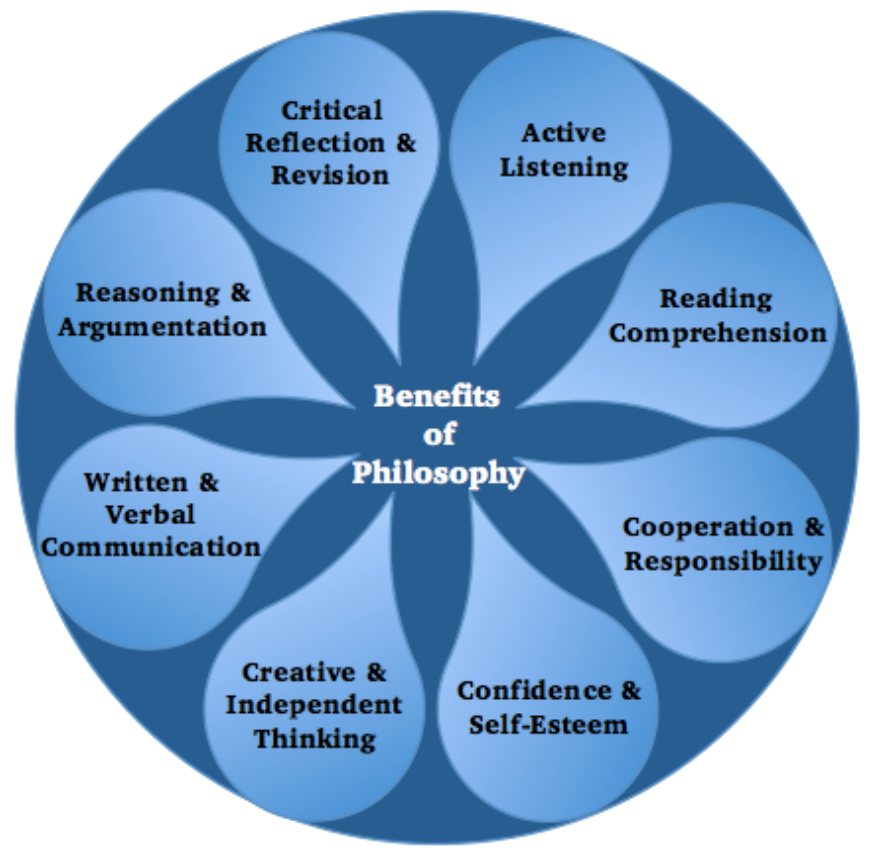

Philosophy helps young people learn how to reason and think well, and to hold respectful and rational conversations with their peers. Philosophy also helps students learn how to have confidence in their own unique ideas.

![]() Philosophical discussions provide students with opportunities to practice important communicative and social skills.

Philosophical discussions provide students with opportunities to practice important communicative and social skills.

Additionally, young people who participate in disciplined philosophical dialogue can learn to overcome shyness, aggression and attention-grabbing behaviors for the sake of cooperating in a kind of group work they find meaningful.

When engaging in a philosophical discussion, students practice such skills as:

For more about the importance of philosophy for young people, see the page “Why Philosophy?”

The goal of a philosophical dialogue is not agreement or final resolution, but that all participants be able to decide what each thinks is most reasonable, whether those judgments are in line with the views of a majority or a minority of the other participants or is one student’s view alone.

![]() A philosophy teacher should model and prompt careful thinking within a discussion and help students see the structure of their arguments and encourage them to work towards finding the most reasonable answer.

A philosophy teacher should model and prompt careful thinking within a discussion and help students see the structure of their arguments and encourage them to work towards finding the most reasonable answer.

Many different approaches and tools can be used to ensure that the materials used to inspire philosophical inquiry are age-appropriate:

- Children’s literature

- Activities and games

- Film clips

- Stories the children bring to the classroom

- Current events

- Personal experiences

![]() It is important that the materials used in a philosophy session not only present one or more philosophical themes, but also present them as contestable – preferably, a variety of perspectives on the theme should be represented.

It is important that the materials used in a philosophy session not only present one or more philosophical themes, but also present them as contestable – preferably, a variety of perspectives on the theme should be represented.

![]() Facilitating philosophy sessions in schools requires someone who is curious and loves thinking about complex ideas, but doesn’t think s/he knows everything!

Facilitating philosophy sessions in schools requires someone who is curious and loves thinking about complex ideas, but doesn’t think s/he knows everything!

The following are some helpful resources for deepening your philosophical awareness.

For more resources on doing philosophy with young people, check out our Media and Reference Library!

The Problems of Philosophy

by Bertrand Russell

This slim, classic volume offers an overview of philosophical issues including the nature of reality and the value of philosophy. It does not touch on ethics or social or political philosophy. This work is best for adult readers.

Buy Now »

What Does It All Mean? A Very Short Introduction to Philosophy

by Thomas Nagel

Even slimmer than Russell’s classic, this modern overview of philosophical issues is an easy read for most adults and high school students, and probably by many upper-level middle school students. As the author puts it, “This book is a brief introduction to philosophy for people who don’t know the first thing about the subject.” Nagel’s chapters consider nine problems of philosophy, in a very engaging style.

Buy Now »

Socrates Café

by Christopher Phillips

Phillips began the Socrates Café movement, which sets up adult philosophy discussion groups at bookstores and other free-access public venues. Phillips’ book is based on the idea that philosophy is something you do –through debate and discussion – rather than simply study, a very appropriate approach for young people. Questions spotlighted in this book include: “What is insanity?” “How do you know when you know yourself?” “What is a world?” “Does anyone have the right to be ignorant?” and “Why question?” Because the tone is colloquial rather than scholarly, it helps those without a philosophy background grasp the nature of philosophical discussion.

Buy Now »

The following activities and thought experiments can be used to facilitate philosophical discussions during advisory periods. They are designed to get students thinking about a range of philosophical questions and most can be completed in one advisory period. Lessons that are longer or with multiple parts can be spread over several sessions. For ease of planning, several lessons have been split into multiple sessions to accommodate the shorter advisory periods.

Objective: To engage students.

Descriptions:

Ethics

Think of something that’s pretty good.

Now think of something that’s better than pretty good, that’s good.

Now think of something that’s better than that, that’s really good.

Think of something that’s pretty bad.

Now think of something that’s worse than pretty bad, that’s bad.

Now think of something that’s worse than that, that’s really bad.

Now think of something that’s both good and bad.

Now think of something that’s neither good nor bad.

Epistemology

Think a big thought (about something small)

Think a small thought (about something big)

Think a really hard thought (about something soft)

Think softly. Can you?

Think a funny thought

Think a serious thought

What is a thought?

Aesthetics

Write down something that you think is beautiful and two reasons why you think it’s beautiful and write down something that you think is ugly and two reasons why you think it’s ugly.

Can something that’s beautiful also be ugly?

Something that’s ugly also be beautiful?

Metaphysics

If you had to describe yourself using only 5 words, what would they be?

Write them down.

Have class share them.

Objective: To think about the right rules or norms to guide classroom discussions. This exercise attempts to give students the opportunity to formulate rules that they themselves would choose to be governed by.

Description:

Session 1:

Begin by talking about rules and what their purpose is. One way tol motivate the discussion is by reading Chapter 12 (“The Schoolroom”) from E.B. White’s classic, Stuart Little. In this selection, Stuart, who, in spite of being the son of human parents, looks exactly like (and is the same size as) a field mouse, has taken a one-day job as a substitute teacher. He proposes to his class that he would like to be Chairman of the World and asks them what rules they think ought to be instituted. Stuart’s students suggest rules like “No stealing,” “No being mean,” and “Don’t kill anything except rats.”

In the classroom, discuss the pros and cons of such rules, much as Stuart does in his class.

Session 2:

Pass out index cards to the students and ask them to envision a classroom in which they were bound by only one rule. What rule would that be? Students should then write down their one rule on the notecard they’ve been given.

Session 3:

Once students have formulated their rules, collect the notecards and then, after mixing them up, pass them back. Each student should now have a rule that he or she didn’t write. In groups of two, students then work to come to an agreement about which of their two rules they would choose to be bound by.

Session 4:

Before the advisory period, write on the board the rules decided on by the groups of two in the last session.The class then has to pick five rules that they will choose to be bound by for the remainder of the class. (Let them know, though, that they will always have the option of reconsidering the rules they choose; if good reasons can be given for changing them and the class can agree that changes are warranted, rules can be changed.)

Ultimately, students end up voting for the five rules they prefer; often there is some overlap among the five. For instance, “Respect others” and “Respect others’ ideas” can lead to a discussion about whether there’s a difference between respecting a person and respecting a person’s ideas; some students might think that it amounts to the same thing. Still, they may want to keep both rules.

Objective: To look at the world in ways we usually don’t. You can use it as a way to illustrate to students the way in which philosophy encourages us to examine the world from a variety of perspectives.

Description:

Session 1:

Break the class up into groups of three or four. At each group, one student is designated to write down the answer that the group as a whole comes up with.Then hold up some common everyday household item. (A favorite item to use is a rotary cheese grater, but you can also use things like an eyeglasses case, a blackboard eraser, a pencil sharpener, and even a shoe.)

The groups are then given 3 minutes to think up and write down everything they can imagine using the item for—besides its originally intended function. Encourage them to imagine themselves in different settings: for instance, what could they use the item for if they were out in the wood? If they were 3 feet tall? If they were an ant? If they lived in prehistoric times? If they were with their siblings?

Go around the room and have the students discuss a selection of their favorite answers. If appropriate, ask them to demonstrate how they would use the item in the way they have indicated.

What is the object? Is it still a cheese grater (or whatever the object was)? What makes it so?

Objective: To think about the nature of reality and what we mean when we say something is “real.”

Description:

Session 1:

Break the students up into groups of three. Put the following list on the board and ask each group to come up with at least one thing that fits in each category. Make sure groups don’t discuss or share their answers as they will use these responses in a game in the next session.

- Something that isn’t real but seems to be real

- Something that is real but seems not to be real

- Something you can’t tell if it’s real or not

- Something that has to be real

- Something that is both real and not real

- Something that it doesn’t matter if it’s real or not real

Session 2:

On day 2, make sure students are in the same groups. Each group takes turns reading aloud one of their items, with the students in the other groups having to guess in which category the item belongs. Points are given for the correct guesses, and the group with the most points at the end wins the game. If a group guesses wrong and wants to challenge the other group’s category choice, they can explain why they think the item should be in another category and see if they can convince the group they are right. If they successfully do so, they are given the point.

Objective: To think about the differences between what it means to “know” something and what it means to “believe” it.

Description:

Session 1:

Ask the students to write down three things they know and three things they believe. Once everyone has their statements, have them talk in pairs about their claims and why they put them in the category they did. This should get them started on the difference between knowledge and belief. Then have the whole group come together and have the pairs offer examples of what they agreed were beliefs and what they agreed counted as knowledge. List them on the board under Knowledge and Belief.

Session 2:

Ask the group:

- Do they agree with all the statements as listed? Why or why not?

- What does it take for something we believe to count as knowledge?

- Can we know something we don’t believe? Why would we say we don’t believe it?

- Can we ever know things? Can we be wrong about the things we thought we knew?

Objective: Thinking about and practicing careful communication.

Materials: A blackboard or whiteboard to draw on, blank pieces of paper for students to draw on, crayons or colored pencils if possible.

Description:

Session 1:

Pair students up, and then have them arrange their chairs back-to-back so that one of the members of the pair faces the board and the other faces away. The student who faces away from the board needs to have a surface to draw on (usually a notebook), a blank piece of paper, and something to draw with. A crayon or marker is ideal since students will eventually display what they draw to their classmates, so something bright and easy to see from across a classroom works best.

The explanation of the exercise goes something like this: “The way this exercise works is that the person facing away from the board is a painter, but you cannot see anything except what you are painting. The good news is you have a set of eyes to help you, the person who is facing the board. I am going to draw a picture on the board and you, the painter, will try to recreate it. However, you can’t look at what I’m drawing; only your “eyes” can do that. Your “eyes” will have to describe to you what I’m drawing. You need to keep in mind two rules: first, the “eyes” cannot look at your paper, and second, the painter cannot look at what I am drawing. Students should feel comfortable engaging in a discussion with each other, but do so in a kind of “stage whisper” since, with many students talking simultaneously, the room can get loud.”

Commence drawing a picture on the board. Do so slowly, one or two lines at a time, so that the pairs of students can keep up. Any picture is fine, but something simple works best, for example, a simple little scene with a house and a mountain and a tree — the sort of drawing a small child would make.

When the drawing is completed, make a box around the whole picture to indicate that it’s finished. Invite the painters to look at what has been drawn and to see how close their drawing is to the original. Ask all the painters to come to the front of the room and display their drawings. Then facilitate a question-and-answer session about what worked and what didn’t and how, perhaps, painters and “eyes” could do a better job of communicating and listening.

Typically, painters commend their “eyes” for giving precise instructions, especially for describing what to draw in terms of recognizable shapes, like triangles, squares, and easily identifiable objects like clouds and letters. The most common complaint is that their “eyes” gave confusing information about the placement — right, left, up, or down — of items in the drawing. Brainstorm together about how to build upon what worked and improve upon what didn’t for the next go-round.

Session 2:

Students get back into their pairs, with the former “eyes” now playing the role of painter and vice-versa. This time around, it’s interesting to draw a much less easy-to-follow drawing. (Usually, we draw a cartoon head. Unlike the first drawing, this one doesn’t have easily identifiable objects like trees and houses. Typically, therefore, students have a far more difficult time recreating the drawing.)

At the conclusion of this drawing, again invite the painters to compare their works to the one on the board. Ask them to come to the front of the room and again display what they’ve done. (Without fail, the drawings are more interesting this time around, even though they tend not to look very much like what was drawn on the board.)

At this point, lead a discussion about why this time around was so much trickier and what could have been done to make it easier for the painters to match the drawing on the board. (Sometimes, a discussion about the nature of art emerges here. Students often want to talk about whether the pieces in the second round — which admittedly look little like what was drawn on the board — aren’t, in fact, more interesting works of art than those in the first round.) Often students want to talk about whether a painter has “failed” if his or her artwork doesn’t match the original picture. Occasionally, some students get very exercised about their drawing (or their partner’s) not looking like what the teacher has drawn. From time to time, this can lead to a rich discussion of whether it was fair that the second time was so much harder. A teacher might put this up for grabs as a topic to inquire about: is it fair that some people face harder challenges than others? If so, why? If not, why not? What if facing those challenges leads to superior outcomes (like more artistic drawings?) Would you rather be an expert at something simple or a novice at something complex?

Objective: Learn to support claims with reasons.

Description:

Session 1:

Hand out two or three index cards to each student. Then ask them to write their names on each of the cards and then to write on each card one claim they believe in. Ask that at least one of these claims be a normative claim. Talk with the students beforehand about what normative claims are; the idea is to write down something they believe people ought or ought not to do, or something that is right or wrong. Once they’ve written down the claims, ask them to write down, on the other side of the paper, three reasons they have for believing the claims to be true.They have about 10 minutes to do this and can appeal to whatever outside sources of information they want during this time. Tell them to make sure they give three different reasons for their belief. Encourage students to not share their claims or reasons with others as they will be used to play a game in the next session. Collect the cards.

Session 2:

Before class, divide the cards in half and then divide students into two teams based on the two piles of cards. You keep the cards, making sure to keep the cards from the two teams separate from each other. Then tell them the rules of the rest of the game. The goal is for students to be able to guess what the claim is from the reason(s) cited for believing it.

Starting with Team One, read the team one of the three reasons from the one of the cards from Team Two. They have a minute or two to decide together on a guess for what the claim might be. If the students can guess the claim from the first reason, Team One gets 3 points. If they guess it after hearing the second reason, they earn 2 points, and if they need all three reasons to guess the claim, they earn 1 point. If the students can’t guess correctly, the team earns no points. If the guess is close but not exactly right, sometimes they can earn a half point.

The game is fun and lively. Students enjoy trying to guess claims from the reasons offered for them. And they generally do a pretty good job of it. Sometimes disagreements arise about whether a reason offered for a claim is a good one. This is great — encourage discussion about it.

Objective: To think about the relationship between appearance and reality, and the value of authenticity.

Description: In his book Anarchy, State and Utopia, American philosopher Robert Nozick developed the thought experiment, The Experience Machine: Suppose there was an experience machine that could give you any experience you desired. Your brain would be stimulated when hooked up to the machine so that you would think and feel that you were doing anything you wanted to do: playing on a major league sports team, being a famous actress, skiing on a fabulous mountain, being the lead in a famous rock band, writing a great novel, etc. When you’re hooked up to the machine, you won’t know you are – you’ll think that it’s all actually happening. Your experience will feel just as real and vivid as your experiences feel to you now.

Would you map out how you would like your life to go and then hook up to the machine for the rest of your life?

Objective: To think about the ethics of taking something that doesn’t belong to you.

Description: This is a thought experiment from The Pig That Wants to Be Eaten (2005, p.40) by Julian Baggini.

When Richard went to the ATM, he got a very pleasant surprise. He requested $100 with a receipt. What he got was $10,000 with a receipt – for $100.

When he got home, he checked his account online and found that, sure enough, his account had been debited by only $100. He put the money in a safe place, fully expecting the bank swiftly to spot the mistake and ask for it back. But the weeks passed and nobody called.

After two months, Richard concluded that no one was going to ask for the money. So he headed off to the BMW dealership with the hefty down-payment in his pocket.

On the way, however, he did feel a twinge of guilt. Wasn’t this stealing? He quickly managed to convince himself it was no such thing. He had not deliberately taken the money, it had just been given to him. And he hadn’t taken it from anyone else, so no one had been robbed. As for the bank, this was a drop in the ocean for them, and anyway, they would be insured against such eventualities. And it was their fault they had lost the money – they should have had safer systems. No, this wasn’t theft. It was just the biggest stroke of luck he had ever had.

- What should Robert do? Return the money or buy a new car?

- If Robert keeps the money, does it matter how he spends it?

- Is Robert stealing? What does it mean to steal?

- Does it matter that the money is from a bank? What if it was from an individual?

Objective: To think about the differences between what we need and what we want.

Description:

Session 1: Describing Wants and Needs

Give the students a worksheet with the following questions:

- What are some things you want?

- What are some things you need?

- What is the difference between what you want and what you need?

- Do all people have the same wants?

- Do all people have the same needs?

- What should we do if what one person wants conflicts with what another person needs?

Give the students sufficient time to think about their responses and write them on their worksheets.

Session 2: Distinguishing Wants and Needs

Make two lists on the board: wants and needs. Ask the students to suggest items for these categories from their worksheets. This generally spurs a discussion about the difference between wants and needs and whether something that is a want for one person could count as a need for another. What is the difference between wanting something and needing something?

Objective: To think about what makes music beautiful or not

Description:

Session 1:

Ask students each to choose one or two songs they think are beautiful, and one or two songs they think are ugly, and to think about why. Then ask them to share their songs and their reasons for choosing them in small groups of 4. Invite students to ask thoughtful questions to other group members about their song choices.

Session 2:

Facilitate a large group song share. Invite student volunteers to first say a little about one of their songs and why they think it’s beautiful or ugly, and then play a minute or so of it, and perhaps sometimes the entire song.

This leads to a discussion of what makes something beautiful and/or ugly, what it means for something to be beautiful or ugly, why music is so meaningful to us, and other issues of aesthetics, but it also allows students to see one another in new ways and to share something of themselves that often ends up being very personal.

Objective: To think about what makes someone a good person.

Description:

Session 1:

Think of someone you know who you think of as a good person. What makes this person a good person? List at least three qualities of the person. In small groups, share your lists and generate a list of 3 qualities that the group more or less agrees upon. They don’t have to reach consensus as there will be an opportunity to discuss with the full class.

Session 2:

In a large group share, list each group’s qualities on the board and facilitate a discussion on whether any, some, or all of these qualities make someone a good person. Check with the class if they can think of any qualities that are missing from the list and why they might be important. This can lead to a rich discussion on what it even means to be a good person.

Objective: To think about hopes and dreams.

Description:

What is your hope? Show this short video and ask students to answer the prompt, “What is your hope?”

Objective: To think about personal identity.

Description:

Session 1:

- Write down something you know about yourself.

- Write down something you don’t know about yourself.

- Write down something pretty much everyone who knows you knows about you.

- Write down something hardly anyone who knows you knows about you.

- Write down something that you think is important that people know about you.

Encourage students to share their answers (to the extent they are comfortable) in small groups asking them to notice any patterns in people’s responses.

Session 2:

Facilitate a whole group discussion about the questions discussed in small groups in the previous session.

Objective: To reflect on gratitude and what it means to be grateful.

Description:

This is an exercise that works well in the weeks just before the winter holiday break.

You’re given a sweater for your birthday that you don’t like.

- Should you be grateful?

- Do you always have to be grateful for a gift even if you don’t like it?

- Are there limits to gratitude?

- Does it count as being grateful to express gratitude you don’t genuinely feel?

Objective: To reflect on aspects are salient to your personal identity

Description:

Go through the thought experiment Staying Alive with your students. At each stage, ask them what choice they would make to stay alive, which is the aim of the game. After students share their choices (a quick poll can be helpful here), ask them their reasons. Each round of the thought experiment can be done in one session, making this a three-session lesson.

Objective: To encourage students to consider what makes something art, and to examine the issue of intentionality in art.

Description:

Have each student draw two pictures. One drawing must be a drawing they would call art, and the other one they would not call art.

Once the students have finished drawing, ask them to share their pieces and explain what makes one art and the other not. Ask the students listening to the sharing student: Do you think this (intended not to be art) piece could be art? Why or why not?

Step One: Choose a prompt that will be read aloud to the group. Write several questions related to the prompt on the board before breaking the group up into small groups of three. Give each group a poster board and each participant a marker or pen (different colored markers is ideal).

Start by explaining that this is a silent discussion and there will be time to speak in both the small groups and the large group later. Let the participants know that once you have finished reading the prompt, the rest of the activity will take place in silence, with each participant using a pen to communicate their thoughts and ideas to one another on the poster board. The questions on the board are starting prompts, and they should feel free to respond to some or all of these and/or to add their own questions.

After the prompt is read aloud, the group responds to the questions and/or comes up with new questions, using the poster boards. The silent, written conversation can stray to wherever the participants take it. If someone in the group writes a question, another member of the group can address the question by writing on the poster board. Participants can draw lines connecting a comment to a particular question. More than one person can write on the poster board at the same time. Participants can write words or draw pictures, if drawing is an easier way to express a particular thought. This part of the activity takes about 15-20 minutes.

Step Two: Still working in silence, participants leave their groups and walk around reading the other poster boards. They can write comments or further questions on other poster boards. This part of the activity takes about 10 minutes.

Step Three: Silence is broken. The groups rejoin at their own poster boards. For about 10 minutes, each group has a verbal conversation about the comments written by others on their board, their own comments, what they read on other poster boards, and the activity itself.

Step Four: Debrief with the large group and discuss some of the philosophical issues raised.

- What did you think of this activity?

- How comfortable were you staying silent?

- Did silence add to or detract from having a rich exchange?

- What philosophical questions that arose seem particularly interesting?

|

Strategy |

Description/Notes |

|---|---|

|

John Davitt’s 300-ways teaching |

We highly recommend exploring this wild list of possible creative formats for expressing an idea!! https://docs.google.com/document/d/1L9EiqnytBIBq3HWteMB3wndGcEiRNRfreAWMzMl2sqA/edit |

|

Zines aka Philozines |

Little subversive booklets to be created as exploration of philosophical questions https://jual.nipissingu.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2017/12/v11223.pdf |

|

Drawing in Response to a Prompt |

You can ask students to draw as either a way to begin or to close a philosophical exploration of a concept or question. Some examples: Draw a home Draw a friend Draw something you want/draw something you need Draw something for which you are grateful/not grateful |

|

Visual Representation Cards |

Visual Representation Cards: Using 3×5 index cards, and any kind of media, ask students to make something with their hands that reflects what is in their minds. This is a chance to reflect your thinking visually, and then to discuss what that means. Are there some thoughts that are better expressed without words? |

|

Save the Last Word for Me |

Give students a collection of posters, paintings, and photographs from a particular time period and ask them to select three images that stand out to them. On the back of an index card, students should explain why they selected this image and what they think it represents or why it is important. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/save-last-word-me |

|

Art and Not Art |

Give students two pieces of paper. On one they should create something they consider to be art, and on the other somethin they think is not art. Share and discuss. https://www.plato-philosophy.org/teachertoolkit/what-is-art/ |

|

The Painter and Their Eyes |

One student (“the eyes”) can see an image being drawn on the board, and another student faces the back of the room and tries to create the image from the eyes’ verbal description. https://www.plato-philosophy.org/teachertoolkit/blind-painter/ |

|

Create Your Home |

Students draw their homes or decorate prepared house outlines, leading to discussions about the nature of home and identity. https://www.plato-philosophy.org/teachertoolkit/activity-create-your-house/ |

|

How Does Music Make a Character? |

Students listen to a piece of music, draw a character whose theme it could be, and make up a story for them. You can extend this with embodiment, having students act, move, and speak as the character would. https://www.plato-philosophy.org/teachertoolkit/how-does-music-make-a-character/ |

|

Eye Catching |

Lay out many different images on a table and allow students to pick a piece that catches their eyes, then discuss in groups or pairs what drew them, what the artist may have been trying to communicate, who may have created it, and who they may have been trying to appeal to? |

|

Embodying Thoughts and Feelings |

Embodiment can be used to communicate emotions and/or ideas evoked by philosophical questions. Ask students to express with their bodies their thoughts or feelings in response to a particular prompt or question. |

|

Spectrum (vs Binary) Embodiment |

You can have students place their bodies, using the classroom space, on a spectrum from strongly agree to strongly disagree in response to a question. As they discuss the question, they can move if they start to change their minds. Build on this by comparing how students would feel if they were forced to think about their responses as binary. What would change or be lost/gained? |

|

Four Corners |

Make the four corners of the class four different answer options to a particular question and let students move around the room and discuss within the groups in each section. |

|

Circle Sculpt |

Inspired by Boalt’s Theatre of the Oppressed, student “scuplt” their or their peers’ bodies to convey a message, then the meaning is interpreted. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=cie_capstones |

|

Theater of the Oppressed |

A host of activities that can be used in philosophical inquiry. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=cie_capstones |

|

Philosophy and Art in Museums: Embodiment and Art Engagement |

Lots of activities related to art and aesthetics. Some ideas: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ea279yEldB-KRhWshtqrhmoly6yP6zCyz-pwN8-xkMs/edit# |

|

Strategy |

Description/Notes |

|---|---|

|

Music Mixer |

After giving a discussion prompt, play music and tell students to move and dance around the classroom. When the music stops, students will discuss the prompt with the student to whom they are standing closest. |

|

Passing Notes |

Have everyone write a question down on a note paper and fold in half. Play music, and once it starts, students begin passing notes around a circle. Then the music stops, keep the note you have and open it. Go around the circle. If each student can answer the question, they do. If not, they ask the whole class. |

|

Jigsaw |

Students break into small groups and discuss a topic, then groups jumble so that one representative from each original group remains, and new groups discuss what their former groups discussed, and look for connections. |

|

Save the Last Word for Me |

Students write on index cards ideas/questions/quotes that stood out to them from a prompt. Then discuss in groups their interpretations of the chosen ideas, saving the last word for each card writer to explain why they chose it. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/save-last-word-me |

|

The Pyramid |

Students start by thinking about their ideas, then they pair off and discuss, then pairs connect to other pairs to discuss, and so on until two sides of the class share their ideas, and then it goes to full group discussion. |

|

Domino Discussion |

Students all share in a circle, and look for patterns in thought before entering a large group open discussion. https://ablconnect.harvard.edu/files/ablconnect/files/01_ch1_resource_domino_discover_ed.pdf |

|

Affinity Mapping |

Pose a question. Students generate responses by writing ideas on post-it notes (one idea per note) and placing them in no particular arrangement on a wall, whiteboard, or chart paper. Once lots of ideas have been generated, have students begin grouping them into similar categories, then label the categories and discuss why the ideas fit within them, how the categories relate to one another, and so on. |

|

Strategy |

Description/Notes |

|

Think (or Write), then Pair, Share |

After a question is asked, students are given time to think, or write individually, then share in a pair, then share with the whole group. https://www.cal.org/siop/pdfs/lesson-plans/using-the-siop-model-to-address-the-language-demands-of-the-ccss.pdf |

|

Wait time! |

Improves quality of student responses and brings in more student views. |

|

Small Group Work |

Students work on a task or question in small groups before sharing with the whole class. |

|

Turn and Talk |

Students turn to a neighbor to discuss before sharing out with the group. |

|

Scaffolding with Sentence Stems |

Sentence starters for students to use to keep a discussion going. https://www.facinghistory.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/Keep_the_Discussion_Alive.pdf |

Created by Emma Macdonald-Scott with contributions from Jana Mohr Lone

Connect With Us!